- Home

- Danielle Henderson

The Ugly Cry

The Ugly Cry Read online

Also by Danielle Henderson

Feminist Ryan Gosling

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © 2021 by Danielle Henderson

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Henderson, Danielle, author.

Title: The ugly cry : a memoir / Danielle Henderson.

Description: [New York, New York] : Viking, [2021]

Identifiers: LCCN 2020043842 (print) | LCCN 2020043843 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525559351 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525559368 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Henderson, Danielle. | African American women—New York (State)—Biography. | Grandparents as parents—New York (State) | Women television writers—United States—Biography. | New York (State)—Race relations.

Classification: LCC CT275.H5573 A3 2021 (print) | LCC CT275.H5573 (ebook) | DDC 305.48/89607471092 [B]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020043842

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020043843

Book design by Lucia Bernard, adapted for ebook by Cora Wigen

Some names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

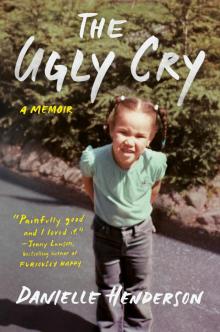

Cover design and hand lettering: Elizabeth Yaffe

Cover photograph: Annette Lacey

pid_prh_5.7.0_c0_r0

For Cory

All that we survived.

Don’t think I forgot about you filling a water gun with piss and shooting it at me just because it didn’t make it into this book, though.

Contents

Cover

Also by Danielle Henderson

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Introduction

I’ve never seen my grandmother bake a cookie, wear a shawl, give good advice, or hug a child unprompted. I have, however, heard her curse so intensely I swear she was making some of them up on the spot, watched her obsess over horror movies with an academic intensity, and listened to her frequent lectures about the reasons every woman should not only carry a knife at all times but also fully be prepared to use it: “A man wants to put his hands on you? Carry a little secret knife. Cut his throat. Ask questions later.” Her favorite TV show is The Walking Dead; she likes to confidently conjure up strategies to survive the zombie apocalypse from her wheelchair, all of them involving rigged-up weaponry and fire. She knows she would triumph; after a lifelong cultural diet of Creature from the Black Lagoon, Creepshow, Hostel, and Saw, she has no problem thinking up ways to kill anything that moves.

And I was raised by her.

It wasn’t planned that way. I had a mom once, and, along with my brother, we had a life together. When she left us at my grandparents’ house for a weekend, none of us knew that she wouldn’t be coming back. I certainly didn’t know that I would spend the rest of my childhood with people who had already retired and thought their child-rearing days were over in the 1970s.

In the whiplash of trauma and figuring out how to adjust to this new life, dropped into the care of a foul-mouthed retiree, I realized it was up to me to figure out how to survive.

So I would take respite in the bathroom, the only sun-filled room in the house, where I could read in relative peace.

Every single person in my family yelled at me when they saw me carrying a book into the bathroom, which I did constantly. No matter what my business was in there, I usually sat on the toilet reading until my legs went numb. I shared a bedroom with Grandma, a twin bed under each window. It wasn’t exactly my own space; she had already made me take down my Led Zeppelin poster, not wanting to look at “those sweaty white boys” on the few days a week she crawled up the steps instead of falling asleep on the couch. The bathroom was the only true privacy I had in the entire house.

“Dani, no—other people have to use the bathroom, you know,” Grandma said, her lips pulling into a terse line as I walked through the living room.

“So then knock,” I said, annoyed.

“Are you giving me lip, child? The library is right down the road! If you’re in there for more than ten minutes, I will knock down that fucking door, little girl!” Grandma called after me.

When I wasn’t letting my legs atrophy on the can while I finished chapter after chapter, I pulled back the shower curtain and climbed into the old bright blue clawfoot tub, using any towel hanging up behind the door as a pillow. I fell asleep in there once and woke up to Grandma standing over me. All of the skeleton key locks had long been painted over in this old house; none of the doors locked. It was easy to burst into any room if, like Grandma, you didn’t value basic human privacy as a rule.

“Oh no, uh-uh, you are not allowed to sleep in the tub and hold this goddamn bathroom hostage when you have a perfectly good bed upstairs.” She was pulling down her polyester, elastic-waist pants before I could even fully get the sleep out of my eyes, and farted loudly as she sat down on the toilet.

“Ew, Grandma!” I yelled, scrambling to stretch my long leg over the side and get out of the tub.

“Should’ve thought about that before you stayed in here for two hours,” she said, gently unfurling some toilet paper. “You can sleep anywhere, but this is the only place I can shit.”

1.

My mom and dad met in drum corps; I have no idea what instrument he played or even if he was any good. It would be weird if I did, since I don’t even know what he looks like. His name was Carlton; he lived in Newburgh, about forty minutes away from Greenwood Lake, the small New York town where my mother grew up. They met at a parade. My grandmother didn’t know that my mom had a boyfriend until he showed up to take her to her junior prom. There’s a picture of them from that night, one of the only ones to survive my grandma’s wrath; Mom was wearing a floor-length white dress with navy blue polka dots, afro picked out as wide as her shoulders. My dad was tall and handsome in his brown corduroy suit, the wide collar of his white button-down threatening to consume his shoulders. His afro was smaller, but the flash cube from the camera made the product in his hair glisten. In true seventies style, the photo is blurry and grainy; I can make out his features, but they don’t add up to anything more than a generic face. They stood in front of my grandparents’ fireplace for the photo, wide-eyed and slightly smiling.

My dad was a year older than my mom, and when he graduated from high school, his family moved to North Carolina. My grandmother chalked up their relationship to a high school romance and didn’t really think of it again. She told M

om to get over it.

But my mom was not over it. Not in the least bit.

The summer after she graduated from high school, my mom got a job dressing up as Wile E. Coyote at Jungle Habitat, a Warner Bros. theme park over the Greenwood Lake border in West Milford, New Jersey. The park was filled to the brim with wild animals, and the main attraction seemed to be that you could watch them roam freely as you carefully cruised by in your car. As you can imagine, this was an idea with a terribly short shelf life; Jungle Habitat closed within a few years amid a litany of persistent scandals. One man was attacked by a lion shortly after the park opened; another woman was bitten by an elephant. Several of the animals got out and were found wandering around residential areas nearby. My mom’s summer job was to dress up like a cartoon and welcome families to this pending horror show, probably taking bets with her coworkers about which of them would come out unscathed by the end of the workday.

At the end of the summer, after she had saved what she thought was enough money to survive, my mom packed a suitcase. She left it behind the shed in the backyard, which was rarely used, so she knew it would be safe. She hitched a ride to work with some friends and came home like everything was normal for the next few days. Then, one morning after she had confirmed plans with my dad—whom she had been in touch with all along—she grabbed her suitcase, acted as though she was leaving for work, and instead took a bus into New York City and another bus from the Port Authority down to North Carolina. At nineteen, she had decided that her life was her own, and she was going to use it to chase a man.

For decades after, my family would ask, “What happened to make her like this?” Mom had a run-of-the-mill, 2.1-kids, stay-at-home-mom kind of family. The kids wore matching outfits for the annual family photo at Sears and were surrounded by cousins, aunts, and uncles at summer barbecues. Grandma had been a different kind of parent to her than she was to me: when I complained about mildly blurry vision as a teenager, Grandma told me that my eyes were fine and “That’s what you get for reading those fucking books all night when you should be asleep.” When Mom needed glasses as a kid, Grandma actually got them for her. Running away was an abnormal event in such a normal childhood. Decades later, my grandma still asks herself what happened, a bubble of self-indictment quietly rising to the surface as she wonders out loud. “She was raised in the same house as your aunt and uncle . . . I just don’t understand,” she whispers, actively searching for a place to lay blame.

For the rest of their lives, they would never receive a satisfying answer.

My grandparents didn’t know where my mom was for three months. It was so well-orchestrated that when she disappeared, nobody suspected a thing—my grandparents, assuming she was dead on the side of the road somewhere, waited for the day they’d get a call telling them her remains had been found. Grandma started going gray. Granddad stopped talking.

“It probably took ten years off of all of our lives,” my grandma said, recounting those months. “I was a wreck, your grandfather was a wreck, Rene and Bobby were so sad. Fucking selfish, in the end, you know? All that misery for a penis.”

After contacting the police and filing a missing-persons report, my family sat and waited. It wasn’t until my grandma got the idea to check the phone bill that they got any relief. “I saw all of these long-distance calls from around the time she went missing. I thought, ‘Who the hell is she calling?’ So I dialed the number, and she picked up,” my grandma said. “Just as happy as a clam, like nothing had happened. I said, ‘Robin, where the fuck are you?’ She told me she was in North Carolina with Carlton.” Grandma was getting annoyed retelling the story. “I don’t know why, but I asked her, ‘Are you pregnant?’ She said yes. Just like that. I told her she better fucking stay there and slammed down the phone.” My grandma seethes with anger when she tells this story, even now, almost fifty years later. “I didn’t raise my children to be like that.”

My older brother, Cory, was born in February 1976. My father was already cheating on my mom by then, and her life in North Carolina was bleak. She lived in a trailer with my dad on his family’s property in a rural town; she couldn’t afford the hospital bill after Cory was born, so she called her grandmother, Sweetie Pie, to wire her some money via Western Union so that she could take him home. He was all she had; she was so lonely she rarely put him down—but even when she held him, he cried mercilessly. She was exhausted.

A few months after Cory was born, my grandma got a letter from one of my mom’s few friends in North Carolina. She said that Robin wasn’t doing so well, but she seemed like she came from a nice family, and maybe she should go home. Again, Sweetie Pie wired her some money, and my mom and Cory took the long bus drive back to New York, almost two years after she escaped.

Granddad met my mom at the bus. He was introduced to his first grandchild on a platform in the Port Authority, surrounded by the noise and grime of New York City. He was so disturbed by the way my mom looked that he couldn’t even speak; he hugged her but didn’t say a word until the next day. She was wearing old men’s clothes and was completely disheveled. Like no one was taking care of her, like she had stopped taking care of herself. Her appearance wasn’t the only surprise my mom brought home with her; when my grandmother looked down, she saw my mom’s belly protruding, like a grapefruit attached to straw. A small tidbit her friend had left out of her letter, but possibly the reason she wrote in the first place.

“Are you pregnant again?” my grandma asked.

My mom nodded.

* * *

—

My grandparents got creative to make space for three kids in their two-bedroom home. They took one of the bedrooms, my mom and aunt shared the other, and my uncle Bobby slept on the screened-in porch. Every single one of your neighbors would call Child Protective Services if you put a child on the porch these days, but this was the seventies, which was basically a lawless decade where children were concerned. Lawn Darts—a game where one child would stand in a Hula-Hoop placed on the ground and another child would aim for the hoop by launching oversize, spiky metal darts at them—hit its peak in this era for a reason: if your child was fed and moderately clothed, people turned a blind eye to your second-degree murder-adjacent shenanigans.

Bobby loved his space on the porch. He had blinds over the windows to cut down on the glare from the lake, as well as a large bookcase that gave him some privacy since the front door to the house was technically one of his walls. Birds used to land on the bushes outside his window, and he would cluck and chirp at them every morning. It was an idyllic room, if you didn’t focus on the fact that it was the only way for every person in the family to get in and out of the house.

My aunt was not so lucky. After having her entire bedroom to herself for her last year of high school, she found herself rooming with her pregnant sister and a colicky one-year-old shortly before graduation. I’m not sure “cockblock” is the correct term; for the sake of my own sanity, I have to believe no one in that house ever had sex. But your pregnant, wayward sister returning like some kind of fucked-up prodigal mess would put a damper on anyone’s lifestyle and make a lesser person lose their mind. Thankfully, my aunt has always been incredible and gracious, and she bonded with Cory immediately. Did anyone ever thank her for that? If someone showed up to my house now, pregnant and with an infant, I would break my own fingers typing into my phone as I tried to find them the nearest Airbnb.

When I was born, absolutely no one was prepared for me to arrive. Pregnancy wasn’t at all like the checklist-heavy micromanagerial bonanza it is today, but you’d think someone would have at least been clocking contractions with mild interest in between popping cans of Tab and smoking cigarettes down to the filter. Mom and Grandma always breathlessly tell the story between bouts of laughter, amazed at my ability to enter the world despite their own ineptitude.

I imagine she had been uncomfortable all day, but for some reason, Mom didn’t tel

l Grandma she was in labor. It was a little over a month before my due date, so it’s possible she just thought she had gas. I’ve never been pregnant, but an extra helping of mashed potatoes is all I need to feel like there’s a bowling ball resting on my spine for the duration of an evening, so I can forgive her. Grandma, true to form, told Mom to stop complaining and go back to bed. Grandma is a medical marvel; she had her motherly instincts surgically removed as soon as Bobby could talk, relieved that she was done nurturing now that her youngest child had an elementary understanding of communicative tools. Not the best person to have on your side if you’re feeling a mild muscular cramp, let alone fully going into labor.

My mom couldn’t sleep, of course, and finally told my grandma she was in labor. “I was so fucking mad because it was the middle of the night,” my grandma says, still upset with me forty years later for waking her up. “They knocked me out when all of my kids were born—called it twilight sleep—so I was always coming to in the morning like a normal person. No one wants to meet a baby in the middle of the night.”

Since neither of my grandparents ever learned to drive, they called one of my grandma’s friends to help get my mom to the hospital. Darlene was white, but she was close enough to the family to get a Black nickname, so I’ve always known her as Nana Dar. She and my grandma first met at a school board meeting and just started talking one day after seeing each other around town. Like most small towns, Greenwood Lake was still a fairly prejudiced place to live—people scowled at my family, and many people wouldn’t let their kids play with my mom, aunt, and uncle. But my grandma was bored and needed a friend, so she did her best to make friends. Nana Dar had a reddish bouffant hairdo and icy blue eyes that set off her olive skin. Like my grandmother, she smoked constantly; I can barely picture her without imagining a curl of smoke drifting up from her chin and dissipating in the air above her head. She was probably smoking when she showed up after midnight to take my mom and grandmother to the nearest hospital in Goshen. Nana Dar and Grandma were definitely chain-smoking the entire thirty-minute drive there. My mom was basically in the back seat crowning, and those two were up front, joking about how she better not give birth in the car, all while flicking clouds of ash on my fontanelle.

The Ugly Cry

The Ugly Cry