- Home

- Danielle Henderson

The Ugly Cry Page 14

The Ugly Cry Read online

Page 14

“The green box.”

“For your period?”

“No.”

“Then why am I buying you maxi pads?”

She used her other hand to pull her cheek skin taut and squinted her eyes. “Sometimes you just . . . y’know. Leak a little.”

“Leak what?”

“Will you go to the goddamn store, please?”

Thrusting the ten dollars into my own pocket, I stomped away, slamming the front door. No one ever answered my questions all the way; Grandma told me to look it up in the encyclopedia, and Mrs. Bell made me go to the library during study hall to cruise the card catalog and look up any answers that weren’t contained in our social studies or math books. The World Book encyclopedia people skipped the “Leaking Grandma” section somehow.

I was twelve years old, and I missed my mom. Our bathroom conversations were more fun, back in Greenwood Lake when she would pop out her teeth and blow my mind. Grandma popped out her teeth in an old-lady way, expected and unimpressive. Would Mom make me buy her maxi pads? The last time we had lived together, I hadn’t been old enough to go to the grocery store alone.

She still called sometimes. If Grandma answered, I could tell it was Mom on the other end by the way Grandma sucked in her breath and said, “What do you want?” before shoving the phone at me. “Your mother,” she’d say, glancing at the TV during the handoff. She only talked about Mom’s absence when she was annoyed at something she had to do for us, like school shopping. “Your mother should be doing this,” she’d grumble while I shoved my feet in the shoe-measuring contraption at Buster Brown. I didn’t talk about Mom with Cory, whose life still seemed to carry on effortlessly in her absence. Mom disappeared from our day-to-day lives, the phone our only reminder, our only connection.

Mom’s voice disarmed me. She sounded the same, like nothing had happened. I wanted to be tough, to give only monosyllabic answers and feign indifference while she told me about her new job at the discount store on Gun Hill Road, the offices she sometimes cleaned at night, the job Luke found that he would no longer have by the next time she called. She spoke with the same lilt in her voice, the same nasal way she called me Dani. The same Mom.

I cried despite myself.

“Take it in the kitchen,” Grandma said, unable to hear her show over my anguish. I looped my fingers around the empty space in the back of the phone and dragged the long cord into the kitchen. I tried to keep it down as I asked Mom when she was coming to get us between sobs.

It was always the same answer: soon. Or maybe, she ventured, she would come get me and Cory to live with her in the city.

I cried harder. Mom tried to tell me the city wasn’t bad, I’d get used to it, I’d make friends. She didn’t realize I was crying at the thought of living with Luke again. I didn’t tell her the extent of what he did to me; she was living in this fantasy of a family, ignoring the rot at the center, making us lie and cover for all the abuse Luke inflicted on us. I couldn’t even process that she was excited about reuniting with me and Cory—she still lived with Luke, and I didn’t trust her anymore.

She tried to soothe me by telling me how fantastic her life was. She was doing well. Everything was great. She loved me and missed me and couldn’t wait to see me. I was spinning in space, living life backward and upside down, getting used to the fact that she could be perfectly settled while we were apart. When I first moved in with Grandma and Granddad, I desperately wanted to go back to a time when it was just the three of us, for Mom to finally, for once, choose me. But she was fine without me. I ended our phone calls with less hope each time.

I kicked a rock on my way up the hill to Main Street and left it at the corner when I crossed to go to the Grand Union. I hadn’t yet gotten my period, and I certainly didn’t want to get it—I cared less about preparing my body for the children I already knew I did not want to have and more about the pain-in-the-ass monthly maintenance of the whole bloody display. I made a silent vow as I dodged a car backing out of a parking space: if I still had my period by the time I was as old as Grandma, I would have a plug surgically implanted or have all my reproductive organs ripped out. And if I started leaking, I would lower myself into a shallow grave, pull loose dirt over my body, and smother myself to death.

The automatic door whooshed open. I knew exactly where to go, but first I had to do my rounds. I cruised by the vegetables to the deli counter at the back of the store, then started weaving in and out of the aisles to make sure I didn’t see anyone I knew. Buying maxi pads was embarrassing enough; buying maxi pads in plain view of Mitra McLaughlin’s mother was a devastating blow to the psyche. The last time Grandma asked me to buy her pads I quickly rounded the corner on my way to the cashier and ran into Irene, one of her old card-playing friends from Greenwood Lake.

“Hi, Dani!” She glanced at the box of embarrassment tucked under my arm like a football. “You’re getting to be such a big girl.”

It was bad enough that I was still very much a little girl, with a body so tall and flat I had corners, but it was even harder to explain that I was buying these pads for her possibly incontinent friend. I’d just smiled and walked away instead, my cheeks burning as I shook my head to cast off the shame of discovery.

The coast was clear. I made my way to the last hurdle. I skipped the teenage cashiers—older siblings of the assholes I had to sit next to every day—and waited until I could scope out the oldest woman standing behind a register. “Brown bag, please,” I corrected as I watched her put the pads in a plastic bag that was too transparent for such a delicate purchase. She looked at me from under her nest of hairsprayed, frosted blond bangs, and handed me the plastic bag.

I walked quickly across the parking lot. The green box of Always pads was like the light on the dock in The Great Gatsby, signaling to all who were near that right in their midst was a twelve-year-old girl dying of embarrassment.

I bolted into the house, where Grandma was pacing in the living room. “What the fuck took you so long! I’m going to be late for work!” She’d finally had to find a job, as it became clear we weren’t going anywhere, and she ended up at Mount Alverno, a sort of retirement home for nuns, run by the Franciscan Sisters of the Poor. Grandma worked in the Greenbrier Room, a big dining hall that served catered meals every day to anyone who could afford it.

She grabbed the bag out of my hands and walked toward the bathroom. “The store is three minutes away—it shouldn’t take you damn near an hour to get these,” she called over her shoulder.

She not only sent me on the most embarrassing errand possible, but she had the nerve to put a clock on it. My mouth was in action before my synapses could spark the part of my brain that knew better.

“You should have told me to rush, then!” I regretted the words as soon as I said them. This was primetime back talk, highest ranking on the endless list of things Grandma would not tolerate. I walked quickly to the living room and plopped on the couch so she wouldn’t have time to physically snatch me, but she was in my face by the time I sat down on the couch.

“What did you say to me, fuck-o?” Her eyes were as wide as her skin would stretch them.

“Nothing,” I said meekly.

“That’s what I thought.” She walked back to the bathroom, a tiny tugboat of righteous anger.

When she made her way back to the living room to grab her purse, I tried a different approach.

“I don’t want to buy those anymore.” It was a moment of extreme stupidity, brought on by my desire to have something in my life that didn’t make me feel so out of place.

Grandma threw her purse over her shoulder and adjusted her black bowtie. Her work uniform was formal, but she had a way of making it look like something a fancy boxer would wear. Grandma in the ring, shirtless and wearing only an industrial bra, elastic-waist polyester pants, slowly pulling off her bowtie as someone slipped in her mouth guard.

“Too fucking bad,” she said, slamming the front door behind her.

* * *

—

Unlike most girls my age, I tried not to consider my body. I didn’t compare it to models’ in magazines. I didn’t pray for my period. I didn’t weigh myself or examine my face carefully in the mirror. I went through most days without thinking about my body at all. So I had no frame of reference when, one morning, I woke up completely frozen.

I was awake, but I couldn’t move a muscle.

I could hear the cable trucks kicking up pebbles against our garbage cans as they pulled into the lot, Jane Pauley starting another hour of the Today show on the TV I had left on all night. Grandma would be upset that I was running up the electric bill, but the voices from the TV made me feel less afraid as I was preparing myself for sleep that would rarely come. I was thankful for cable; the network channels got boring at night, right before they played the national anthem over an image of an American flag and turned off for the night.

I was completely unable to move. I tried talking myself into action. Open your mouth. Open your mouth. If I could scream, someone would come upstairs to see what was wrong. Or, more likely, someone would come upstairs to yell at me for screaming. Still, someone would come if I could move, if I could only move. Open your mouth. Nothing, not even a twitch. The Today show would be back after these messages.

Was I in a coma? Grandma wouldn’t have the patience to sit next to me in a hospital and read books to me like they did in the movies. I would be at the mercy of the nurses and candy stripers. Would my teachers send work to the hospital so that I could stay with my class when I woke up? Or would I be a twenty-year-old with a fifth-grade education, stuck in time? I might not ever wake up; then it wouldn’t matter.

If I could just move my mouth.

I wasn’t moving, no matter how hard I tried. I suddenly had the thought that I should try to go back to sleep—like a hard reset, a do-over. I let the commercials calm me, listening to the TV and the sounds of outside until I went back to sleep.

It worked. According to the Today show schedule, it took almost an hour for me to wake up fully. I felt slightly numb and was vibrating with tension. I waved my hand in front of my face, wiggled my toes, wiggled my jaw back and forth, making sure everything worked the way it did before I was paralyzed.

The sleep paralysis started happening a few times a week. I never got used to it, but I did start panicking less when I realized that it would eventually just fix itself. It could have been my insomnia, or it could have been the aftermath of what I survived. Sleep paralysis was just another thing that kept me connected to Luke, another way my body still felt tied to trauma.

I felt it in other ways, too, like when I found that I couldn’t look at my body in the gym mirror, or the time my English teacher tried to teach us to meditate. The strangeness I felt when I closed my eyes in a classroom full of my peers was compounded by the feeling of waking up around them. I looked at Meg and Amy, both of them repressing giggles. Whatever had just happened, I felt lighter than I did when I walked in the room. But I’d also felt like I’d lost time. Was that the point of this? To lull us into complacency? Anything could have happened while she had us in such a relaxed state. What Luke did to me felt like this—powerlessness, surrender. As quickly as the feeling of lightness washed over me, more intense feelings of shame and anger replaced it. I’m still not at ease in my body. This, too, had been taken from me.

14.

When I was younger, the arrival of summer meant that you were forced to be outside for days on end. As I became a teenager, pop culture had led me to believe that summers were for lazing around, swimming, and snacking. But this white, middle-class worldview was not shared by Grandma. When she was my age, people were still shoving kids down mines without ventilators to stand on tightropes or construct bombs that only their tiny hands could manage, so she couldn’t really stomach the small generational shift that resulted in her granddaughter wanting to read all day. Most days I slept as late as possible, waking up only when the sun rose so high in the sky that the heat streaming through the open windows became unbearable. If I wasn’t up by the time Grandma left for work, she’d shout upstairs and wake me up with her choice of monologues about my useless childhood.

“Dani! Dan-ee-yell! It’s ten a.m.! Get up! You kids think you can sleep all day like there’s nothing to do around here. I’ve never seen such laziness in my life,” she lied. The fact that my uncle—who hadn’t worked in two years—was currently smoking himself to death in the room across the landing shone a bright light on the charade. I would rouse myself enough to stand at the top of the steps and shout, “I’m up,” then take myself right back to bed.

As soon as he heard the front door close, Uncle Bobby always moved from his room to the living room for a change of scenery. It had a bigger TV and the family VCR, so he settled in and commandeered it before I had a chance to camp out for the day. He always had a snide comment for me whenever I dragged myself downstairs.

“It’s one o’clock—don’t you have anything to do today?”

“I’m on summer vacation—this is what I’m supposed to do today. Don’t you have a job or something?”

“Go outside.”

“Get a job,” I called over my shoulder on the way to the bathroom. My uncle and I had a fairly compact “Take My Wife” routine for two people who were not married and couldn’t stand the sight of each other.

Since my friends all lived on the outskirts of town and all three of the adults in my house didn’t drive, I spent most of my summer in town. I would fill my days with walks to the library, reading in silence in my room, and playing Little League softball. Sometimes we would go to the lake with our neighbors. Ben was a kind, intelligent blond kid who loved music; he was in my class, but he mostly hung out with Cory. His single mother, Diane, was a tiny superstar; I liked seeing her Dorothy Hamill bob power-walking down Main Street, almost a foot below everyone else on the sidewalk. She’s actually average in height, but I was already in the process of reaching my full monstrous height, so everyone seemed much smaller. In a couple of years, she would start her own photography studio, sometimes using me as a model for practice, but she had been taking beautiful photos long before she branched out on her own. Diane would pile me, Cory, and Ben into her car and drive us to the lake at Wawayanda. The air felt ten degrees cooler as she curled and twisted the car deep into the woods.

The lake was ringed by tall, lush trees; I liked to dig my toes into the sand, pick a tree in the distance, and try to swim out to it. I never made it all the way across, but the sweeter reward was waiting for me back on the beach, where I’d throw myself on a towel and let the sun warm me as the water evaporated from my skin. No one gave a shit about sunscreen; we rubbed ourselves down with baby oil like fucking idiots and crisped ourselves on bath towels like strips of bacon. For most people, summer wasn’t in full swing until the straps of your bathing suit left grill marks on your shoulders, or you could peel long strips of blistered skin from your back like a sheet of loose-leaf paper. For me, a fair-skinned person with freckles, a hearty sunburn was my way of saying to people, Look, I’ve been outside this summer, at least once. Please don’t ask me to do this again.

My softball games were always at night; this gave parents a chance to see how their recessive traits showed up in their children as we clumsily tried to field pop flies. Grandma showed up once or twice, but I was on my own for daytime practices and most games.

Buying baseball cards was an important part of my week; walking to Main Street and stopping at Dayton’s was sometimes all the sun I would get during the day. Baseball was the only thing that could take me away from books, and spending entire days inside.

Dayton’s was a dusty jumble of a store. It was the kind of place where you could get a box fan, an off-brand radio, hair products recently out of production, scratchy comforters, and plungers.

I stuck to the candy and magazine section. It was the first aisle you hit when you walked in the store, making it easy for the cashier at the raised platform register on the left to see Cory and his friends as they tried to steal Snickers bars.

I always waved to Wayne, the stocky owner with the Friar Tuck ring of graying hair clinging to the sides of his head. He had the worn-down tiredness of a middle-aged dad, but I don’t know if he had any kids. He never seemed to follow or watch me, probably because I had the permanently shame-filled face of someone who would rather throw herself in traffic before stealing anything ever again. I said hello as a matter of course in local friendliness but also to let him know that I knew he was there and wasn’t about to try anything out of sorts. I looked for the new issues of Bop and Teen Beat, Rolling Stone or any magazine featuring a guitar on the front, and sometimes bought a comic book if there was a lady on the front and she looked cool.

“How old are you now?” Wayne was walking by with a box that was big enough to hold a TV.

“Twelve. Thirteen next month.”

He nodded and kept walking, stepping out of the path of a customer on his way to the back of the store.

This time I spied something on the rack that I’d never seen before, or never noticed. Sassy magazine was instantly more macabre than the bright pink, bubble-letter covers of the teenybopper magazines I usually purchased. The logo looked like someone slashed paint against a wall. The articles had weird, intriguing titles, like “Our Writer Knee-Deep in Mud at an English Rave” or “What Jail Is Like for Girls.” The cover model was traditionally beautiful, but with an underlying spookiness in her heavily lined eyes.

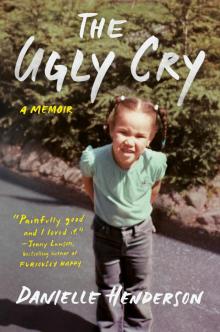

The Ugly Cry

The Ugly Cry