- Home

- Danielle Henderson

The Ugly Cry Page 16

The Ugly Cry Read online

Page 16

“Then don’t worry about how much money Pudge makes. You have enough to worry about,” he said, tapping his pen on the forms, “since your employer didn’t pay any taxes at all for you, and you just found out taxes exist.”

Grandma came back in, raring to go. “Okay, enough, we have things to do before he misses his bus.”

I left the kitchen on the wave of another wink as Showboat and Grandma got to work.

* * *

—

When I finally got the small blue card from the state of New York that said I was eligible for restricted work, a year later, I applied at the local toy store.

I’d never shopped in there; the store opened when I was too old for toys, and they sold expensive brands I didn’t recognize, like Breyer and Playmobil. Most of the toys were made of plain wood or were bright puzzles that were actually homework in disguise. I was hired to work weekends and a few days a week in the summer, switching to only weekends during the school year. My main duties were dusting, straightening up after the spoiled monsters who tore through the store while their uninterested moms talked near the front door, and vacuuming after we closed. I earned $4.25 per hour and worked around ten hours a week. I also started babysitting for Helen Truitt, my coworker.

I worked with Helen most of the time and instantly adored her. She had a calm demeanor, kind blue eyes, and a sick sense of humor that was complementary to my own. One day, I was dusting the counter displays near the register and picked up a giant, hollow plastic dinosaur. I picked a bunch of stones out of the small display of rocks and gems and jammed them in the dinosaur’s open mouth. Helen was sitting behind the register.

“Hey. Hey, lady,” I said in a joke voice, making the dinosaur hop around a little on the glass countertop. “I’m Chunky, the puking dinosaur.” I tipped the toy toward the counter, and all the rocks and gems spilled out while I made fake throw-up noises.

Helen’s laugh started as a low stutter and turned into a full-on shriek. Making her laugh became my favorite reason to go to work.

Chunky the Puking Dinosaur became a constant inside joke, but we lived to make each other laugh through the commonality of our grade-school sense of humor—making sure the Playmobil display figures were always bent over with their butts facing out, pretending all the Breyer horses had diarrhea, or making the dolls recite Kids in the Hall sketches. Helen was a hippie at heart and deeply kind, but nothing made me laugh more than when she would talk in hushed tones about an asshole customer. When she asked if I wanted to babysit her two boys, I said yes immediately.

Unsurprisingly, her kids were as cool as she was. They’d all just moved to Warwick from Bergen County and lived in a sweet house near McEwen Street. Her seven-year-old, Jansen, was a cartoon come to life—he was all red hair, freckles, and boundless energy. Her five-year-old, Ryan, was the sweetest kid I’d ever met—he had big blue eyes and a smile that almost took over his entire face. We mostly played out in the backyard on the swing set; all the kids from the neighborhood would come over when they saw the boys outside, so it was like I was babysitting for five kids at once. They liked science and music, and over the years I always let them stay up a little late to watch Are You Afraid of the Dark? and All That on Nickelodeon. They never gave me a hard time about going to bed or following their parents’ rules about what snacks they could eat. My friends complained endlessly about the kids they babysat, but Jansen and Ryan were easy and cool. Helen’s husband, CJ, was a chef, so I always ate like a champion. Even the leftovers were delicious.

My favorite part of the night was when Helen and CJ came home and told me about where they had been. They went to concerts, dinner, house parties. Sometimes they took turns getting drunk; Helen would come in and send CJ down to the basement immediately. “Someone had too much fun tonight.” Standing in the kitchen together, we’d laugh about the funniest thing that happened with the kids earlier. They didn’t ask me about homework or school like other adults; they wanted to know what I was reading, where I wanted to go after high school, who I hated. I felt like I was being looped into a world where I wasn’t a sad loser kid without a mom who lived with her grandparents, but an interesting person with valuable thoughts.

Helen always checked on the kids on her way upstairs. I couldn’t remember the last time someone checked to see if I was home, safe, and comfortable. They were kind, loving, fun. I thought about how different my life would have been if I had been born into something so normal. I was on the periphery, but the Truitts always made me feel like I was an integral part of what made family work.

* * *

—

Mostly I was grateful that I didn’t have to work at Action Park.

Action Park was one of the most important of all summer initiations for kids in southern New York and northern New Jersey. It was advertised as a water park full of family fun and excitement but was, in reality, a demented, slap-dash horror show built by a conglomerate of Scooby-Doo villains, where every ride could end your life. It was also entirely staffed by teenagers. Cory worked there for a summer, but he refuses to talk about it to this day, like a soldier who returned from the war with PTSD.

Everyone knew that Action Park was a death trap, including the parents who dropped their kids off for the day and drove away, to the point where we all referred to it locally as Accident Park. Parents who stuck around could be found at the Stage, watching has-been bands from the eighties perform their singular hits while getting drunk with the teenagers who were supervising the rides between keg chugs. Then they’d all throw themselves into cars and drunkenly weave their way home, sunburned and reckless. I spent most of the money I earned on cassette tapes but always left a little to go to Action Park at least once per summer, which had more per-minute thrills than any movie could offer.

The place was pure mayhem; we survived winter solely to get to the glorious payoff of summer, where we could watch someone drown in the wave pool, break their back jumping from the rope swing, or slice their legs open at the bumper boats.

The prospect of death was an ominous presence from the minute you walked in the park. There, on the right, was a ride so dangerous it had only opened to the public for a month but stood as a legendary symbol of harm: the Cannonball Loop. It was a long black slide with a single loop at the end. The idea was that you would work your way up the rickety wooden staircase that zigzagged behind it until you reached the top, where a stoned teenager would hose you down with water for the lubrication needed to propel you toward the loop, hopefully with enough velocity for you to clear it. The only problem was that most people didn’t clear it—most got stuck at the bottom, so many, in fact, that a trap door was cut into it to let them out.

Allegedly.

Others dropped from the top part of the loop and broke their necks or cracked their skulls open.

Allegedly.

The biggest rumor we whispered to each other was that the park sent dummies down to test the ride, and they all slid out onto the rubber mat at the end missing arms and legs.

Allegedly.

The rides that were open to the public still contained plenty of chances for dismemberment. The Wave Pool seemed like an innocuous place to take a dip and cool off on a hot summer’s day. A giant concrete slab at one end of the pool slapped the water in lazy intervals, creating waves. They weren’t big enough to surf but were definitely big enough to drown you if you lost focus for even ten seconds. Someone got sucked under once and died being slapped to death by the thick, concrete slab.

The Tarzan Swing could have been a fun, easy way to enjoy the day. Imagine grabbing a thick rope, swaying through the air, and dropping into a cool pool of water.

A normal person would have invented a ride like this, simple and relaxing.

The demented fucks at Action Park built a ramshackle rope bridge that was as stable as a tightrope walk made of dental floss, attached some frayed lengths of rope precariously to

a pole, and made the sign of the cross as legions of children grabbed hold and pushed off. You were lucky if you got to actually hold on to the rope; I mostly saw kids pushing their friends off the edge when they weren’t paying attention, and drunk adults with Ray-Ban tan lines losing their grip and sliding down the entire length of rope, skidding to a stop at the bottom with the first two layers of skin missing from their palms. Bless your heart if you tried a back flip or anything fun that you saw in the commercials; I’d seen enough people carted out on stretchers with neck braces to never be that brave.

I would not personally recommend Roaring Rapids, Action Park’s answer to riding a cushiony tube down a lazy river. The water was freezing, and the unregulated force of the rapids often upended people right out of the tube. Broken noses were not uncommon as people smashed their faces on the jagged rocks below or met the business end of rocks being chucked by teenage boys floating on tubes in front of you, trying to get your attention. (This is how we flirted in the old days.)

Water slides, typically a lackadaisical affair, took a sinister turn at Action Park. I was too afraid of heights to ever try it myself, but Cory likes to say he almost died on the Kamikaze. One of the main attractions of the water slides at Action Park was that they dropped you from ferocious heights, so much so that a length of rubberized fabric had to be stretched over the first twenty feet or so of each slide to prevent you from flying off the edge as you gained momentum. They made you cross your arms over your chest as you lay down at the top—you know, the way they pose people in coffins. “My face skidded on the rubber!” Cory was very excited. There were several bumps and hills on the slides that caused you to catch air as you rocketed toward the bottom or prayed for the sweet release of death, slamming you back down onto the hard plastic slide over and over again, legs and arms akimbo. I never saw anyone arrive at the bottom feet first with their arms still crossed over their chest as they were positioned when they began; they slid down like rag dolls, sideways or upside down, and crying. Always crying.

Action Park was equal parts water and blood, hubris and neglect. There should have been an EMS attendant at every ride and a blood-borne illness check as you left the park. Having already lived with a man who beat me up on a regular basis, I didn’t see the need to flirt with death at Action Park, and I generally kept to the tamer rides. But death comes for us all, and it came for me in the form of the Alpine Slide.

Imagine looking at thousands of feet of ski trails and saying, “You know what this needs? A meandering, solid, concrete half-tube that bakes in the sun all day, where we can send children down at lightning speeds on what amounts to a lunch tray on wheels.” The Alpine Slide was colloquially known as the Skin Ripper, the Finger Smasher, and the Alpine Skinless. In 1980, someone genuinely died on the Alpine Slide; he flew off a malfunctioning sled and hit his head on one of the many, many jagged rocks dotting the landscape around the ride. Action Park was so dangerous that even knowing the nicknames and body count, this was the ride I chose, the one I thought I had the best chance of surviving intact.

I sat on my scooter at the top of the hill. My feet were next to my butt, my knees bent and almost touching my eyes. My back rounded as I hung on to the steel handle, which was somehow both my steering column and brake. A dead-eyed, monotone teenage boy gave me my instructions so fast he may have been the Micro Machines guy.

“Keepyourhandsinsidekeepyourlegsinsideusethebraketoslowdownhaveagoodtime,” he slurred, before giving me a customary shove.

I realized I was going too fast when I hit the first curve. Instead of following the slide, I bounced off the edge, tumbling into the grass. Thankfully, my scooter bounced with me, and I didn’t hit any rocks with my head. I picked it up and positioned myself back on the slide, accidentally rolling over my fingers as I tried to gain purchase and get going again. I pushed the steering column to engage the brake, hoping to have a leisurely ride down to the bottom.

Not only did the brake fail to engage, but the kid rocketing toward me from behind couldn’t stop, either. He slammed into me full force, again sending me over the edge, this time scraping my shoulder against the concrete slide as we tumbled. I stood up on the grass; once I was sure I had all my fingers and toes, I looked at my arm. A thick, red rope of a burn twisted around from my shoulder to my elbow. It stung and was tender to the touch.

The kid who slammed into me was already back on his scooter and near the bottom.

I decided to forgo the rest of the ride and carried my scooter down the grass as reckless idiots whizzed past me. I wasn’t averse to scars, but I was freaked out at the thought of dying in a driving accident before I even had my license. This is smart, I thought. I’m being safe. Now that I was making my own money, Grandma couldn’t prevent me from using it to tempt death all summer.

I ran to Roaring Rapids after I got to the bottom of the slide, dipping my arm in the disease-ridden churn as my inner tube bobbed along. The cold water really felt good on the burn. I was part of it now, the grand scale of insanity disguised as fun, baptized in blood and fear. I had tried to follow the crowd, and now I was done. I went back to Action Park a few times to spend a day outside with friends, but I never went on the rides again.

* * *

—

As I saved my paychecks and faced my faced my first year of high school, I looked at this stage of my life as another hurdle before I reached my ultimate goal: graduating and getting the fuck out of Warwick. At some point, I’d read about Drew Barrymore getting emancipated from her mother and was consumed by the thought that I might one day get to live on my own. I envisioned decorating my walls with Led Zeppelin posters, going to bed anytime I wanted, sitting on the toilet with a good book for hours if I felt like it, and eating pizza for every meal—which is not far off from how I live as an adult. More than anything, I thought that living alone at fourteen years old would bring me the peace and solitude that I had not yet experienced in any iteration of living with my family. I broached the subject with Grandma.

“Drew Barrymore got emancipated from her mom.”

I threw myself into the chair in the living room, while Grandma sat on the couch, smoked her cigarette, and flipped through People magazine, not reacting to me at all.

I continued. “She lived on her own and was just a teenager.”

Grandma lifted her head and stared at me, as if to say “So fucking what?”

“She was just a teenager,” I reiterated, “and I work, so . . .” I let the sentence trail off, hoping that Grandma could make the logical leap with me.

“And how, exactly, would you afford an apartment?”

“I have a job. And I’ll get another one.”

“When would you work if you go to school?” Grandma kept staring at me while she took a long drag.

“I’d keep the schedule I have now,” I said enthusiastically.

“So you can pay for rent, electric, gas, garbage, water, heat, and food on your little twenty hours a week?”

“. . . Yes.” I had no idea what I was talking about.

“That girl is a millionaire. You want to move out on babysitting and toy store money? Be my guest.”

“Well, how much does electric cost?” I was determined to make this work.

Grandma tutted, went upstairs. She came back with a stack of envelopes tied in a rubber band from the gray two-drawer filing cabinet in our bedroom. This was the intricate system she used for all her important paperwork—just jam it together and tie a rubber band around it, then throw it in the filing cabinet.

“Here,” she said, wrestling an envelope out of the stack. I noted the Orange & Rockland logo as I slid the piece of paper out, then unfolded the bill. In a large font at the bottom, it read: amount due $150.

“That’s for one month?” My jaw dropped. It took me two jobs and three weeks to earn $150.

Grandma laughed, picking up the Nintendo controller and restartin

g her game. “Yep! That’ll change your tune, huh?”

Living alone was going to take some time. I resigned myself to high school instead.

* * *

—

High school is a big leap—you’re going from the top of the heap to the bottom, the biggest to the smallest at the worst time to make such a change. You’re already navigating painful summer growth spurts that leave you feeling like a newborn foal trying to stand up for the first time, and your face is exploding into a psychedelic array of bumps and oil slicks. Your body starts naturally making the kinds of smells you thought only emanated from dumpsters, and for no reason, several times a day, you feel like a soaked sponge. Preteen emotions operate in two modes: happy and sad. Your new teenage emotional life now includes a palette of shockingly unstable hormonal displays: jealousy, rage, deep sadness, happy crying, utter confusion, planetary worries about the hole in the ozone layer, new bras, balls dropping, and, for some reason, wanting to wander through graveyards as the height of romance. Hair takes on Wolfman-like proportions, teeth are wrangled into place, and your skin starts erupting. Then, one day, you have to drag this melting, exploding haversack of viscera into high school, a landscape filled with people who have already surpassed this horror and come out on the other side glistening like a new car.

If you see a teenager in the wild, be gentle. Every single one, even the coolest among them, is navigating the world like a twitching sack of snakes stuck in the molting phase.

Compared to the middle school, Warwick Valley High School was huge. Anxiety set in early about whether I’d have time to get from class to class as I traversed the wide expanse of the hallways in a sea of people. Other kids were thinking about stories from their siblings, replete with eighties teen movie villains dunking their heads in toilets, giving them wedgies, or shoving cow shit through the slots of their lockers. Like every unpopular, maladjusted weirdo before me, I was already accustomed to feeling wildly out of place—I just wanted to make sure I got a seat before the bell rung.

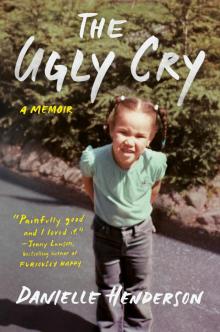

The Ugly Cry

The Ugly Cry